Why we don’t Incorporate Federally

Prospective clients often ask to incorporate “federally” or that they want a “Canadian incorporated” company. In most cases we recommend a provincial incorporation instead – here’s why:

1. Federal Falsehoods

At the start, it’s critical to dispel federal incorporation falsehoods:

First, federal incorporation does not allow the company to operate Canada-wide. Like a provincially incorporated company, a federal company must register in each province in which it does business (see separate nexus test), which involves paying an extraprovincial registration fee to each province (except Ontario, which is free for federal companies). Similarly, provincial companies must pay an extraprovincial registration fee in each province.

Second, federal incorporation does not protect a company name across Canada. The federal government uses the “NUANS” name reservation system, which has been adopted by some but not all provinces (British Columbia, for example, does not use NUANS) such that a federal company name is only protected in NUANS provinces. If you’re looking to protect a company name Canada-wide, the correct approach is to file a trademark.

2. Residency. Federal corporations are required to have a board of directors containing 25% Canadian residents or, if four or fewer directors, 1 resident director. Conversely, certain other provinces do not have director residency requirements, for example British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario and Nova Scotia. As most startups receive foreign (often U.S.) investment, federal residency requirements quickly become a problem.

3. Extra Provincial Registration. Since federal corporations are effectively foreign in all provinces (except Ontario), a federal corporation must immediately pay an additional extraprovincial registration fee based on the first province in which it does business. For example, a federal corporation based in British Columbia must pay roughly $450 in extraprovincial registration fees immediately upon incorporation, which for a cash-strapped startup is an unnecessary expense.

For all the above reasons, consider incorporating in your home province rather than federally (with some exceptions). Before taking the step to incorporate, be sure to speak with your legal advisors to determine which jurisdiction fits your particular needs.

You Don’t Need a US Company to Raise from the US

We’ve attended a number of presentations lately where Canadian founders are told that they MUST be a US company to raise money from US investors. This advice is patently false; Canadian startups raise from US investors all the time and investors generally don’t care that a prospective portfolio company is Canadian.

1. Where does this Falsehood Originate?

10 years ago, US investors were less receptive to investing in Canadian companies. Many funds had a domestic focus due to a wealth of US investment opportunities but as the venture environment became more competitive, and funds ever larger, investors began to look abroad. The historic US focus of funds was often reinforced by restrictions in their LP (limited partnership) agreements that prohibited investments outside the US, with similar restrictions exhibited by incubators such as Tech Stars and Y-Combinator.

2. The Truth: US Investors don’t care that you’re a Canadian Company

Today, US investors in our clients rarely care that they are Canadian companies while most incubators have dropped the requirement that portfolio companies be US incorporated.

Of the 1,400+ companies we represent, we have only encountered 1 US investment that required the company to reincorporate in the US, in all other cases US investors took no issue with a Canadian company or could be made comfortable quickly (often any friction is due to US legal counsel’s lack of familiarity with Canada).

3. US incorporation and Canadian tax Results

Should you still wish to incorporate in Delaware, it’s important to understand that a cross-border, Delaware-Canada, structure may lead to negative tax results for both the company and its founders unless a proper legal and tax plan is created (and followed).

Potential negative tax results include: (a) personally missing out on the capital gains exemption and the roughly ~$1.25 million of tax free gains it offers; (b) the company missing out on certain R&D tax credits (see: Revisiting – Should I Incorporate my Canadian Startup in Delaware); and (c) the company being exposed to costly cross-border legal and tax issues due to bring a US company but operating in Canada.

4. Investors don’t lead with “where are you incorporated?”

Investors don’t lead with “where are you incorporated?”; incorporation jurisdiction is an afterthought. If an investor wants to invest and demands a US company, your lawyers can quickly restructure the Canadian company into a Delaware company. An investor that passes, rather than allowing you to restructure, was never going to invest in the first place.

For more information, please see our posts: Should I Incorporate my Canadian Startup in Delaware and Revisiting – Should I Incorporate my Canadian Startup in Delaware.

Raising Capital from U.S. Investors

Many Canadian companies raise funds in cross-border financings, with most rounds including at least 1 U.S. resident investor (if not a U.S. lead investor). If your Canadian startup is raising funds from U.S. investors, you will need to keep the following in mind:

1. Value Your Startup in USD

All Canadian startups should value themselves in USD. While early investors may be Canadian, U.S. startup to benefit from the USD-CAD exchange rate, further extending runway to the extent expenses (see: payroll) are in CAD.

In our experience: (a) Canadian investors expect a USD valuation; (b) US investors don’t consider forex; and (c) your company is not more appealing because CAD is cheaper – investors are looking for quality companies not forex discounts.

2. US vs Canadian Templates

Most startup financings use template documents, either YC’s SAFE or the National Venture Capital Association priced-round documents (CVCA for Canadians). It’s important to use the correct, Canadian, version of these templates as the Canadian version contains key clauses designed to achieve Canadian legal compliance. The Canadian versions are very similar to the US versions, which similarity will create comfort for your U.S. investors and their legal counsel.

3. Canadian and US Securities Laws Apply

As a Canadian startup, raising company from U.S. investors will implicate cross-border securities laws. First, since your startup is incorporated in Canada, Canadian securities laws apply. Second, since the investor is resident in the U.S., U.S. securities laws apply. It is critical that compliance with these securities laws be addressed before closing a financing. Luckily, cross-border legal counsel should be able to address compliance quickly.

4. You Don’t Need to incorporate in the US

You don’t need to be a U.S. company to raise money from U.S. investors and many U.S. investors won’t force you to be a US company. Of the 1,400+ companies we represent, we’ve only had to incorporate a U.S. company to appease U.S. investors twice in the last 12 years. Read our blog posts on the subject here: Should I Incorporate my Canadian Startup in Delaware and Revisiting – Should I Incorporate my Canadian Startup in Delaware.

Moving to Canada

As a cross-border law firm, we focus on establishing Canadian companies for US (and other foreign) companies; often these cross-border structures are driven by remote teams and/or a desire to utilize certain Canadian tax credits. Our aim with this post is to detail the most common cross-border structure we create for our US clients (especially startups) to establish a Canadian presence and move some of their team to Canada.

1. Form Canadian Entity

First, a Canadian entity is formed, usually in the province where the company anticipates being based. Where there are employees living in multiple provinces, often we will recommend incorporating in the province in which most employees are based.

While Canada has a unique federal corporate structure, we do not recommend incorporating federally as: (i) federal companies are foreign in all provinces, resulting in the need to register the company in each province in which it has a presence and incurring additional legal costs and administrative hassle; and (ii) the board of directors of a federal company must have at least 25% Canadian residents, or if less than 4 directors, 1 must be a Canadian resident, a requirement that may be a challenge for a foreign company to meet.

2. Subsidiary or Affiliate

Second, we collaborate with our US client and their tax advisors on the best ownership structure for the Canadian company. Depending on the client’s needs and desire to utilize certain Canadian tax credits (a common ask for startups), the Canadian company may be a wholly-owned subsidiary or affiliate of the US company.

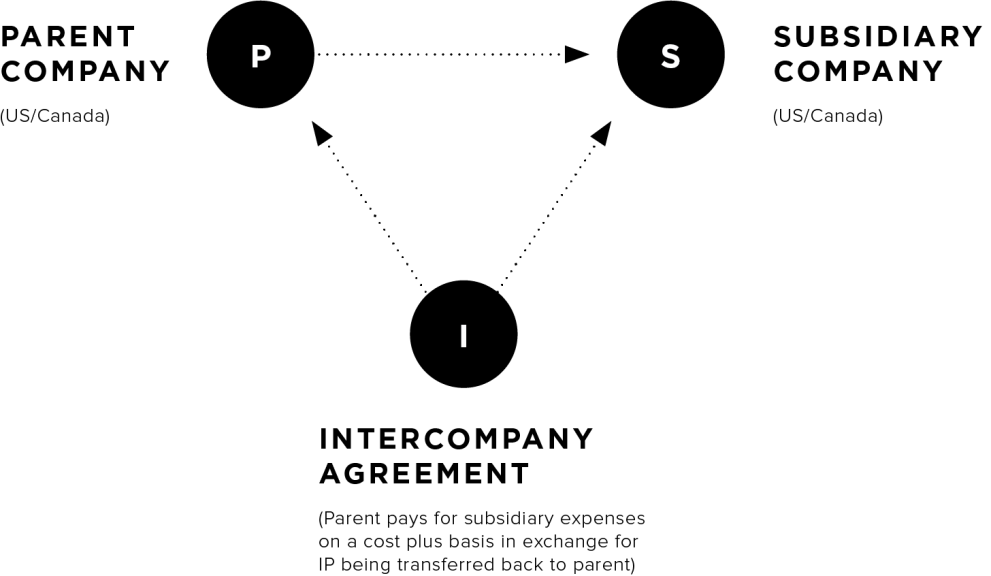

3. Intercompany Agreement

Third, we draft an Intercompany Agreement to address the relationship between the US company and Canadian company. While the two companies are related, they must treat one another on an arm’s length basis for tax purposes.

Effectively the Intercompany Agreement sees the US company paying Canadian company costs, with a % markup, in exchange for intellectual property created by Canadian employees being transferred back to the US company, as illustrated below:

4. Employment Agreements

Finally, we re-draft (Canadian-ize) the US company’s US Employment Agreement template to comply with Canadian laws, which Employment Agreement would then be used by the Canadian company to hire. Through this unique approach (uncommon among law firms) we ensure that the Canadian employment agreement is as close as possible to the US company’s, allowing for substantial contractual consistency between jurisdictions.

If you’re looking to setup Canadian operations for your US company, please reach out to the Voyer Law team and we would be glad to discuss your options in-depth.